Does power corrupt or is something else going on?

When the Green Party was set up in West Germany in the early 1980s, it had a radical platform of ecology, nonviolence, social justice and grassroots democracy. It included a radical plan for candidates elected to parliament: they would serve only one term of office, then step aside for another candidate. But that’s not the way it turned out. Several of the initial Green members of parliament decided to continue in office, flouting the party principle, seemingly in favour of their own careers. Was this a case of power leading to corruption?

Time to quote the famous saying by Lord Acton: “Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” It is widely quoted because it seems to capture something often observed in politics, and beyond. Have you ever known a mild-mannered colleague who, on becoming the boss, became an oppressive bully? But is there any research to confirm informal observations about what power does to people, research that might back up Acton’s saying?

For decades, I’ve been fascinated by studies of power, and read books and articles by various authors. For example, Pitirim Sorokin and Walter Lunden in their 1959 book Power and Morality provided data that government and business leaders were much more likely to commit serious crimes than the average citizen. This sure fits Acton’s saying.

Among academics, one of the most-cited books is Power by Steven Lukes. It is an insightful analysis of concepts, proposing that it is useful to view power in terms of one, two or three dimensions.

The one-dimensional view is the one we usually think of: the capacity to make others do things they don’t want to, for example the power of a boss to instruct an employee. The two-dimensional view includes what’s called non-decisionmaking. Sometimes employees don’t need to be asked. They try to anticipate what the boss wants and do it, without any conscious decision-making process. The three-dimensional view includes structural arrangements. A workplace run with a hierarchical system of bosses and subordinates sets the agenda for all decision-making.

Klaas’ view

A recent book by Brian Klaas challenged my long-standing views. In Corruptible: Who Gets Power and How It Changes Us, Klaas raises a number of objections to the power-corrupts narrative. What if those seeking power were more prone to corruption? What if the earliest Green politicians were the members keenest to become candidates and obtain positions of status and influence? This would be a different process: it would be positions of power being especially attractive to those individuals most easily corrupted.

Corruptible also challenged my view that books about power are pretty boring, of interest only to specialists. Corruptible is entertaining. Klaas travelled the world interviewing a range of people, including brutal dictators, trying to figure out what makes them tick. And he tells fascinating stories about corrupt individuals.

Recruitment to positions of power

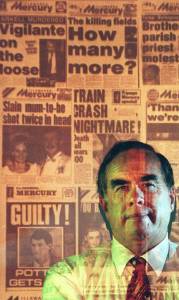

Consider a police department, one where some officers are venal and brutal, taking opportunities to steal and to lord it over others. Think of the officer in Minneapolis in 2020 who held down George Floyd, while he cried out that he couldn’t breathe, for nine minutes until he died. This became infamous, but unfortunately there are lots of other incidents, large and small, in which officers abuse their power.

The beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles police, 1991

Is the problem that police, because they have power, become corrupt, or is it that corruptible individuals are attracted to joining the police? Klaas describes revealing research findings showing how some police job advertisements are more attractive to bullies.

The usual response to police abuses is to institute training, to try to change the behaviour of the officers who have been hired. Klaas describes a different, additional idea: spend more effort recruiting individuals who are different, who normally would not be attracted to a police career, such as gentle, compassionate, honest individuals who are reluctant to use violence. The idea is to avoid recruiting people who are attracted to the sort of power wielded by police.

Maybe the Greens should adopt this approach: encourage the members who are least interested in leadership roles to become candidates for office. Dream on!

Don’t (always) blame the powerful

Klaas offers another challenge to the idea that power tends to corrupt: he notes four things that are commonly overlooked when examining the actions of people in positions of power. The first is “dirty hands.” When Green parliamentarians have to choose between two evils, their vote will cause harm no matter what choice is made. In Australia, the Greens had to decide whether to support or oppose weak legislation on climate change. They either disappoint their supporters for compromising or are condemned for being blockers. Klaas tells of cases in which rulers have had to make decisions and, whatever choice they made, people would die. Not nice, and not about power corrupting.

Another thing commonly overlooked is that those in power have more opportunities to do bad, so they look worse than others. Earlier I mentioned the study by Sorokin and Lunden about political and business leaders being higher than average in criminality. Maybe this wasn’t because they were corrupted by power but because they had the power to get away with murder.

Yet another factor is that people in positions of power are closely observed, so they seem to be up to more mischief. Green parliamentarians receive a lot more scrutiny than ordinary members of the party, so anything they do that’s wrong is more likely to be discovered and publicised. Again, greater scrutiny of the powerful might give the mistaken impression that power corrupts. Klaas summarises his analysis:

“Corruptible people are drawn to power. They’re often better at getting it. We, as humans, are drawn to following the wrong leaders for irrational reasons linked to our Stone Age brains. Bad systems make everything worse. Yet, our intuitions about power can be flawed and mistaken. Four phenomena — dirty hands, learning, opportunity, and scrutiny — make it seem that power makes people worse than they actually are. We sometimes confuse the effects of power with intrinsic aspects of holding it.” (p. 148)

But power does tend to corrupt

After canvassing many challenges to Lord Acton’s comment about power, Klaas finally addresses it, and he agrees with him: power does tend to corrupt. Klaas cites studies showing that gaining power makes behaviour worse, with powerholders interrupting and stereotyping others more, and being more hypocritical.

Klaas says that “for decades, the scientific literature on how power affects us was limited,” but he missed the work of one important researcher in the field, David Kipnis, who carried out careful experiments that showed the psychological effects of having power over others. For example, it makes the powerholder think their subordinates are not autonomous and hence deserve less respect, making them even more vulnerable to exploitation.

What to do

Most academic writings on power focus on analysis, on what it is and how it operates. Klaas does something else: he gives a lot of attention to solutions to the corruptions of power. As well as arguing for the recruitment of individuals who are less susceptible to temptation, he recommends choosing decision-makers by lot, called sortition, like the selection of jurors for a trial. With random selection, power-seekers have no better chances of being chosen than anyone else.

Yet another option is rotation of office-holders. This is just what the German Greens initially planned: elected parliamentarians would serve only one term of office. The Greens couldn’t do it on their own, but what if all parliamentarians were allowed only one term? This would cut corruption, because those in office for short periods are less susceptible to special interests.

Decades ago, I corresponded with an unusual political activist in the US. He sent me leaflets and bumper stickers with the slogan “Re-elect nobody.” His idea was that voters should always vote against whoever was in office. If enough did this, members of Congress would serve only one term. Predictably, his idea never caught on. And it’s crazy to imagine the members of any parliament legislating to restrict their terms of office. They’re not likely to listen to anyone, even if Klaas has a great idea for getting better people into positions of power.

Klaas notes that there are far more studies of disasters than of successes. Assuming for the moment that the Australian Greens opposing a carbon-price scheme in 2009 was a poor decision, Klaas’s point is that there has been much more attention to it than to good decisions by the Greens. He argues that as well as examining the results of decisions, there should be audits of decision-making processes.

“Better people can lead us. We can recruit smarter, use sortition to second-guess powerful people, and improve oversight. We can remind leaders of the weight of their responsibility. We can make them see people as human beings, not abstractions, before the powerful turn them into victims. We can rotate personnel to deter and detect abuse. We can use randomized integrity tests to catch bad apples. And if we’re going to watch people, we can focus on those at the top who do the real damage, not the rank and file.” (p. 246)

I’ve mentioned just a portion of the fascinating material in Corruptible. Even so, there is one topic about which I would have liked more: getting rid of positions of power altogether. It’s often assumed that hierarchies are inevitable, and someone has to be the boss. But there are many examples of cooperative endeavours in which no individual has a great deal of formal power. This is a big topic, so I’ll just mention consensus decision-making techniques, worker co-ops like Mondragon in Spain, participatory budgeting like in Brazil, and all sorts of voluntary groups.

So imagine this. The Greens, instead of trying to get their own members elected to parliament, push for a different sort of decision-making system, one in which no individuals have a great amount of power. Well, it hasn’t happened yet, but it can be added to the agenda for those concerned, like Lord Acton, with power and corruption.

Brian Martin

bmartin@uow.edu.au

Comment from “Alicia Verde,” who has close familiarity with the Greens New South Wales

The Greens have historically had fewer problems with power and corruption than other major parties. Our grassroots focus helps reduce these problems.

However, in the Greens NSW we do occasionally experience those who abuse power, both those who are corrupted by power and those who are already corrupt and seek power for its own sake.

As the Greens NSW Party grew, the career path to becoming an MP (member of parliament) became easier and more attractive, potentially attracting those who desire power, including those who want power for power’s sake. This is far more evident in the two larger Australian political parties for obvious reasons. This defined career path has led to several instances of prospective and elected MPs abusing power.

Any new political party with no guarantee of electing an MP is less attractive to those who are driven to seek power.

Greens NSW enshrined grassroots democracy in its constitution, rather than an MP-focused perspective. That was early on in our formation. I believe it would have been more difficult to achieve this with the current number of MPs.

In the Labor Party and the Liberal-National Party Coalition, power rests in their party rooms, caucuses and party elites. In Australian politics, the Greens NSW are unique in successfully seeking to devolve power from MPs to grassroots membership at the heart of our constitution and processes.

The Greens NSW constitution facilitates dealing with toxic MPs by any local group bringing a proposal to a state delegates council (held six times a year) that can reprimand or, as happened on at least one occasion, force an MP to resign. This is despite MPs having considerable soft power (instinctive deference to MP opinions) within the party. There is constant pushback against soft power due to a significant commitment to a non-hierarchical structure. Though this isn’t easy, the Greens’ consensus decision-making model can be effective in dealing with power-related toxicity, far more so than in the other major parties, that either rely on popular votes or have a structure that effectively silences voices from the membership.

Yes, power does tend to corrupt, and yes, absolute power corrupts absolutely. It’s inherent that MPs start to believe their own media, while sycophants prop up their egos. However, it really gets toxic when external groups with vested interests become involved, such as via political donations, which the Greens don’t take from corporations. These donations enshrine and feed power imbalances; the corporations need the imbalance to protect their influence. This is a really corrosive problem in Australian and Western democracies, corrupting even those who are not “power-hungry.”

Given inherent problems with power corrupting groups, it is the robustness of the structures and processes underpinning organisations that count to derail the corrosive aspects of power.

In Greens NSW, what helps to ensure that a non-hierarchical perspective is not eroded over time is the constitution and the willingness of state delegates councils to dictate policy, reprimand abuses or over-reach, plus party members’ wariness of those in power and of power itself. This has enabled maintaining policy positions on many very difficult issues and reduced the “protecting my re-election prospects” agenda where MPs are conflicted in difficult situations.

On limited terms for MPs, this was contemplated in Greens NSW but rejected as it also serves to end the careers of some really great MPs. It can be a double-edged sword.

Randomly selecting MPs would be effective if it were also for the entire parliament but this would mean abandoning our Westminster system for something far more progressive, which is not an option in the next few years I imagine! Sadly!