Some of Wollongong’s most prominent figures were involved in sexually abusing boys. Residents might never have known about it except for media stories.

I’ve lived in Wollongong since 1986, yet there are lots of things I don’t know about the city. Some of the things I do know about, or think I know, are mainly due to news reports. One of them is paedophilia in high places.

News reports in the 1990s revealed that a previous mayor — the elected head of the local government — had run a paedophile ring, and another previous mayor was a suspected paedophile. These revelations were so striking that I saved some of the newspaper reports about them. Recently I read them again. They paint a grim picture, and provide a lesson in how a city’s public face can conceal horrible activities.

Here I summarise some of the media revelations, focusing on three individuals: Tony Bevan, Michael Evans and Frank Arkell. Links are given to articles published at the time, which give more details.

Bevan

On 9 March 1995, the front page of the Illawarra Mercury — Wollongong’s only daily newspaper — had a huge headline: “Former mayor ran child sex ring.”

Tony Bevan had been mayor and a pillar of the community. He died in 1991, leaving behind numerous tape recordings he had made of conversations with politicians, businessmen and other paedophiles. These tapes were obtained by the Mercury. The newspaper published transcripts of some of the recordings. The story summed up the findings in this way

Bevan ran a paedophile “school” where Illawarra and Sydney boys were seduced and manipulated. They were then used to sexually service Bevan and his friends.

Bevan and his paedophile associates in Sydney controlled a youth refuge where boys were kept before being sent to work as prostitutes in Kings Cross [a Sydney red-light district].

Bevan was involved in bringing young Filipino boys to Australia to work as prostitutes.

Bevan pimped for influential Illawarra, Australian and foreign paedophiles — offering boys who provided sexual favours.

An international paedophile network exists that allows those “in the club” to access boys worldwide.

The Bevan Tapes also identify 15 Australian paedophiles associated with Bevan as well as a number of corrupt officials in the Philippines.

Evans

On 22 July 1995, the Sydney Morning Herald — the most prestigious daily newspaper in Sydney — ran a story titled “Brotherly love.” It told about the Christian Brothers, a Catholic religious order, which runs schools throughout Australia. In particular, the story told about some members of the Christian Brothers who had been accused of paedophilia. The lead character in the story was Michael Evans, who in 1982 became head of Edmund Rice College, a Catholic boys high school in Wollongong.

During his years in Wollongong, Evans became its most prominent Catholic figure. Then in 1993, a story in the Illawarra Mercury about an alleged indecent assault ended his career ambitions. Evans left town. In 1994, he was served with an arrest warrant over an indecent assault on a teenage student. The next day he committed suicide.

From 1995 to 1997, there was a royal commission into the New South Wales Police Service, often called the Wood royal commission. It was not one of those inquiries that quietly reinforces the status quo. Unusually, it was a crusading commission, using its extraordinary powers to shine a spotlight on police corruption. The public hearings received saturation news coverage.

Among other things, the commission looked into policing and paedophilia. As reported in a front-page story in the Illawarra Mercury on 17 April 1996, a priest testifying at the commission criticised Wollongong’s Catholic Bishop William Murray and a high-ranking police officer for not acting against Evans. It was reported that even before being appointed head of Edmund Rice College, allegations of sexual abuse had been made against Evans. The church hierarchy did not act on them. The police had also been notified, but Sergeant David Ainsworth decided not to take action.

Media coverage stimulated the police to reopen the case. A 20 April 1996 story in the Sydney Morning Herald summed up what happened after allegations about Evans were made to the bishop.

… Brother Evans’s career, far from being stymied, flourished in the years that followed. He had a popular Sunday night radio program …, wrote a column for the Illawarra Mercury, opened the youth refuge Eddy’s Place in 1988 and basked in the image of a man dedicated to caring for Wollongong’s youth.

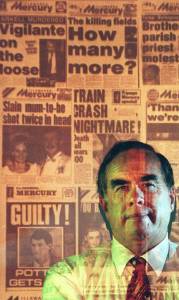

The Illawarra Mercury played a major role in exposing prominent figures who were paedophiles. The editor-in-chief at the time, Peter Cullen, took the lead in both exposing and condemning sexual abuse in the church. A Wollongong priest, Father Peter Comensoli, was sentenced to 18 months in prison for sexually molesting teenage boys. In a column castigating the church for leaving open the possibility of Comensoli returning to the priesthood, Cullen concluded by writing

To this day, none of Comensoli’s victims, their parents or family have received any communication from the Catholic Church expressing sorrow or regret at what happened.

Not a line, not a phone call. They are still waiting.

Peter Cullen in front of Mercury headlines

Another Mercury story reported on testimony before the royal commission by Bev Lawson, chief superintendent, who commented critically about Wollongong police not following up in their investigation of child sexual abuse allegations. Sergeant David Ainsworth had left messages with the bishop asking for an interview. The bishop didn’t respond, and Ainsworth decided not to pursue the matter.

It seems that, in Wollongong, leading figures in the Catholic Church and in the police were reluctant to investigate allegations of sexual abuse. The media, and media coverage of royal commission hearings, were what pushed matters along.

Arkell

Frank Arkell was mayor of Wollongong from 1974 to 1991. He was widely known for his promotion of “Wonderful Wollongong,” taking every opportunity to advocate for the city, which went through difficult times economically, especially in the early 1980s.

After losing office in 1991, things went downhill for Arkell. In 1994, he was accused in state parliament of sex offences. During the police royal commission, he was called to give evidence but pleaded illness. The commission, with other matters at hand, decided not to pursue him further. But subsequently police mounted a case against him.

Then on 28 June 1998 there was a spectacular headline in the Sun-Herald, a major Sydney Sunday newspaper: “Child sex MP slain.” Arkell had been murdered in his home, beaten to death. His Rotary badge was stuck in an eye and tiepins were stuck in his cheeks.

Arkell’s murder opened the floodgates for reporting and commentary. Arkell was dead and couldn’t sue for defamation, so gloves were off. The lllawarra Mercury ran eight pages of special coverage, with the main story by editor-in-chief Peter Cullen. Cullen wrote:

Some of our community leaders are saying Arkell put Wollongong on the map.

I agree. He did. But for all the wrong reasons — for his double life, the sinister side which resulted in his being charged with sex offences against teenage boys, now grown men with their lives torn apart.

Arkell’s life is over. For some of his victims, their lives finished years ago.

Arkell was relentless in blaming The Mercury for his fall from grace. At every opportunity he condemned the newspaper, pleaded with people not to buy it, and said he would not stop until we answered for our sins.

He had sued for defamation.

We were not fazed by that and intended to defend our wicket with every resource at our disposal.

However, let’s get a few facts straight. It was the Wood Royal Commission and its investigators who caused most of Arkell’s heartache.

They produced three alleged victims, all strangers to The Mercury. They went before the commission under code names and made damning allegations against Arkell.

Yet, when Arkell had the chance to enter the witness box and refute the allegations, he ducked it.

Instead, he produced a statement and his solicitors presented a sick certificate to the commission as a reason why Arkell could not attend.

The following day The Mercury interviewed Arkell, and he told us he felt fine.

In other stories after Arkell’s murder, the question was raised whether the media, once the restraint of being sued for defamation was removed, had been too harsh on Arkell. Another story asked why people in Wollongong did not seem appalled at Arkell’s murder.

In August, a lengthy story, “City of secrets,” appeared in the Good Weekend, the magazine of the weekend edition of the Sydney Morning Herald. The author, Richard Guilliatt, linked Wollongong’s working-class masculinity and Catholic morality with the seamy activities that had been revealed by the royal commission.

It now transpires that Wollongong was run for 20 years by two mayors who preyed sexually on their teenage constituents, and that a raft of well-to-do figures — the headmaster of the local Catholic boys’ college, a local councillor with five children, a rotund industrialist who drove around town in a Rolls-Royce, a Catholic priest, a local restaurant manager, a shark-patrol pilot — molested dozens of boys for years with apparent impunity.

Guilliatt pointed out that homophobia was very strong in Wollongong, especially compared to Sydney. Bevan and Arkell would never have been elected had they been openly gay. In 1984, Arkell actually voted against legalising homosexuality. Ironically, said Guilliatt, Arkell would have had a stronger defence against the allegations against him if he had acknowledged being gay: he could have said he was mistaken about the boys’ ages.

Guilliatt questioned some of the allegations about Arkell, who might have been found not guilty in court. The “vigilante” who murdered him pre-empted the verdict.

I have no way of judging the allegations myself, though one of my colleagues told me that one night he witnessed Arkell leaving the Council building at midnight, with a young boy on each hand.

The Council building in Wollongong

Lessons

One lesson from these stories is that public figures may not be what they seem. Even in private they can lead double lives. According to news reports, some of Bevan’s friends had no idea anything untoward was happening, and a longtime friend of Arkell’s thought he was heterosexual.

One reason Bevan, Evans and Arkell were able to maintain their public façades for so long was that the church hierarchy and the police did little to act on complaints about abuses. For those who had been abused, or who knew them and heard their stories, it seemed no one in authority was willing to act.

The role of the media was crucial. To my knowledge, no academics have investigated the Wollongong story. For a blow-by-blow account of the murder of Arkell, and two related murders, see John Suter Linton, Bound by Blood: The True Story Behind the Wollongong Murders (Allen & Unwin, 2004).

In 2012, former Edmund Rice College Brother John Vincent was sentenced to at least six years in prison for sexual offences in the 1980s.

Apparently, in the media the allegations were known for a long time, but nothing could be reported because of the risk of being sued for defamation. The result is a tainted legacy: after Bevan, Evans and Arkell died, their reputations were trashed. Some might say deservedly so, but they were no longer around to contest claims made about them.

In Wollongong, media revelations occurred because the editor-in-chief of the Illawarra Mercury, Peter Cullen, personally campaigned against paedophilia. In the Sydney media, those opposed to homophobia were caught in a bind. Paedophilia in high places was a big story, but it could harm the struggle for gay rights.

There was also another factor, highlighted in Gulliatt’s story about Arkell. He had done more than anyone else to promote Wollongong, especially when its fortunes were at an ebb. To raise allegations about his personal life could also harm Wollongong’s reputation, in a process of guilt by association. Some people may have preferred that the paedophilia story be quietly forgotten.

If you know about criminal or unethical action by people in high places, what should you do? This is especially difficult if your own status has been tarnished. It is seldom easy to admit being duped or abused. Many of those victimised by paedophiles felt ashamed, and their lives had gone downhill. Who will believe you? Who should you trust to take action?

In the Wollongong paedophilia chronicles, the answer was not the police and not the church hierarchy. The most effective avenue for redress was the media, even though the resulting publicity did not offer the protections of a court trial. But surely trial by media was preferable to the vigilante justice that claimed Arkell’s life.

Postscript

Things may be better in Wollongong. There haven’t been as many stories about high-level paedophiles. Edmund Rice College is under new leadership. Homophobia is less vicious. Perhaps Arkell’s sales pitch of “wonderful Wollongong” is more credible these days. But who knows for sure?

Brian Martin

bmartin@uow.edu.au

Sources (in chronological order)

Brett Martin, “Former mayor ran child sex ring,” Illawarra Mercury, 9 March 1995, pp. 1, 6–8.

Richard Guilliatt, “Brotherly love,” Sydney Morning Herald, 22 July 1995, Spectrum pp. 1A, 4A.

Paul McInerney, “Priest damns bishop, senior police officer,” Illawarra Mercury, 17 April 1996, pp. 1–2.

Richard Guilliatt, “Sins of the Brothers,” Sydney Morning Herald, 20 April 1996, p. 25.

Peter Cullen, “Catholic Church should defrock this molester,” Illawarra Mercury, 20 April 1996, p. 7.

Paul McInerney, “How the police blew it,” Illawarra Mercury, 23 April 1996, pp. 1, 4–5.

Liz Hannan and Anna Patty, “Child sex MP slain,” Sun-Herald, 28 June 1998, pp. 1, 6–7.

Peter Cullen, “Vigilante on the loose,” Illawarra Mercury, 29 June 1998, pp. 1–8.

Kate McClymont, “The demise of a double life,” Sydney Morning Herald, 29 June 1998, p. 15.

Pilita Clark, “The media and the murder,” Sydney Morning Herald, 4 July 1998, p. 33.

Stefanie Balogh, “Killer wins kudos in a city as hard as steel,” The Weekend Australian, 4–5 July 1998, p. 12.

Richard Guilliatt, “City of secrets,” Sydney Morning Herald, 22 August 1998, Good Weekend pp. 22–28.

(Some of the these citations include related stories by other authors.)

Some informative more recent treatments

Peter Newell, “Long struggle to expose evil abuse of children in the Illawarra,” Illawarra Mercury, 17 November 2012.

Angela Thompson, “Edmund Rice College was ‘a dumping ground’ for child sex predators: Stephen Jones MP,” Illawarra Mercury, 16 June 2016.

Nick McLaren, “Frank Arkell: how a vicious murder unmasked a city’s darkest secrets,” ABC Illawarra News, 26 June 2018.