Behavioural addictions are on the rise. It’s important to understand and be able to change them.

It’s commonplace to see people walking along with their eyes focused on their smartphones. Surveys show that many check their phones the last thing before going to sleep and the first thing when they wake up. And they have them within arm’s reach the whole night.

Some online gamers refuse to take a break, playing for days and nights on end. Playing the game becomes more important than eating or sleeping.

Is it reasonable to refer to obsessions of this sort as addictions? If so, they are addictions to behaviours, not substances.

For insight into this rising problem, check out Adam Alter’s new book Irresistible. The subtitle explains the topic: Why we can’t stop checking, scrolling, clicking and watching. The book is highly readable, though not quite as irresistible as the activities Alter describes.

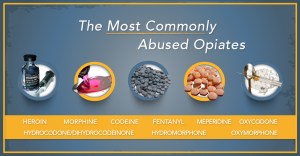

To provide a context for understanding behavioural addictions, Alter examines the more familiar sort of addiction, to drugs. The usual idea is that the physical processes involved are the key, including wanting the drug and having withdrawal symptoms. In relation to pain medication, Alter says something more is involved: a psychological component, in particular emotional pain. Alter says addiction “isn’t the body falling in unrequited love with a dangerous drug, but rather the mind learning to associate any substance or behavior with relief from psychological pain.” (p. 89) For example, people who were sexually abused as children may cover up the emotional pain by using drugs.

So what’s involved?

“Behavioral addiction consists of six ingredients: compelling goals that are just beyond reach; irresistible and unpredictable positive feedback; a sense of incremental progress and improvement; tasks that become slowly more difficult over time; unresolved tensions that demand resolution; and strong social connections.” (p. 9)

Alter devotes a chapter to each of these six ingredients. One of the fascinating insights is the way designers try to make activities enticing.

Consider poker machines, in which players put in their money in the hope of winning a prize, especially a jackpot. Research shows that near misses provide an incentive to keep playing. Even so, there are fallow periods with no wins during which players are inclined to quit. In the US, gambling establishments are prohibited from manipulating the odds. So instead of the machine giving a little payout just when a player was thinking of quitting, an employee, watching the proceedings, will provide a small gift, such as chocolates. Even this process can be automated, with the machine providing information to the proprietors as to when to offer a gift to a player.

Gambling addictions involve unpredictable positive feedback, but there is not incremental progress and improvement. For greater behavioural addiction, skill is involved, and skills improve.

Video games are the most common type of behavioural addiction. The most engaging games are very easy to learn, provide pathways for gradual improvement but make it impossible to achieve total mastery: there is always another level of difficulty. Alter interviewed video game designers. Some of them became addicted to their own games, and so did everyone else around them.

Television producers try to induce viewers to keep watching a serial by using the technique of “unresolved tensions that demand resolution”, more commonly called cliffhangers. Near the end of an episode, some new development – an unexpected phone call, illness or assault – will be provided so viewers will want to tune in to the following episode to find out what happened next, namely to resolve the tension. This technique helps explain the popularity of soap operas and quite a few TV series. However, watching a show once a week is not a big problem. The addictive qualities of cliffhangers become more obvious when entire series are available on demand. Some viewers watch two or more episodes at once, or even binge for several days.

Knowing about the cliffhanger technique, a bit of planning can overcome bingeing on multiple episodes. The key is to end the viewing session after resolution of the tension, maybe 5 or 10 minutes into the next episode, and then start there the next time.

Alter provides numerous tips for overcoming or avoiding addictive behaviours. Email is a common problem: as soon as there’s a notification of an incoming message, it has to be checked or willpower is needed to resist checking it. One solution is to disable notifications. An even stronger technique is to shut down email altogether for most of the day, only opening it for a limited time. Alter counsels against the aspiration of an empty inbox, because this goal encourages obsessive checking of emails.

It’s now possible to buy all sorts of monitors, for example to record your pulse and the number of steps you’ve taken. Setting goals is fine, but Alter warns about making them too precise. When setting yourself the goal of 12,000 steps in a day, there’s a risk of injury by over-exercising. The target goal can overshadow messages from the body about exhaustion or pain. Self-monitoring runs the risk of encouraging addiction.

Who is susceptible?

It used to be thought that drug addicts had weak personalities and that to break an addiction, all that is needed is the assertion of willpower. These views are thrown into question by evidence that the environment makes a huge difference in addictions. Alter refers to the heroin users among US troops in Vietnam during the war. On returning to their home communities in the US, very few maintained their habits. The implication is that changing an addict’s environment is central to change. This includes being around different people and avoiding the triggers for the habit.

With behavioural addictions, environments are changing in ways that make more people susceptible. Video game addiction occurred from the earliest days of gaming. It was often thought that young males were especially vulnerable. But the reason they were more commonly addicted was opportunity. Not having jobs or other responsibilities, and having access to game consoles, they could devote hours to gaming every day.

Therapists who treat gaming addicts have noticed an explosion in addiction in the US since the arrival of the iPhone in 2007 and the iPad in 2010. Suddenly many more women and older men began developing addictions. The reason: access to games has gone mobile. No longer anchored to a console, you carry your device with you. It’s like having drugs on demand, with no cost.

For substance addictions, one treatment option is abstinence. It’s possible to totally avoid alcohol or heroin, and this is the basis of twelve-step programmes, most famously Alcoholics Anonymous. However, treating Internet addictions through abstinence is not feasible, because jobs and other activities so commonly involve operating online. Alter canvasses various ways to deal with Internet addiction. Many of these draw on insights about how to change habits.

The difficulty of changing habits points to a strange discrepancy. Powerful groups seek to promote behaviours, like checking Facebook, that serve their interests, but that can become addictive. There are relatively few groups dedicated to countering these potentially addictive behaviours. Furthermore, there is even less effort put into helping people break damaging habits.

It’s worth thinking broadly about damaging habits and challenges to them. Smoking is the classic example. Tobacco companies benefited from hooking people on smoking and it has taken extraordinary efforts by campaigners to bring tobacco addictions under control. A key part of the change has been to make ever more spaces non-smoking. Another part has been to stigmatise smoking.

Alcoholism remains a scourge on many people’s lives. Alcohol producers so far seem to have avoided many of the controls applied to smoking.

Then there are illegal drugs such as marijuana, heroin and ice. The prohibitionist impulse is a manifest failure, enabling the rise of organised crime with disastrous consequences for users and their families.

With the vast expansion of behavioural addictions, what are the choices? Internet companies benefit from behaviours, like checking phones regularly, that easily become addictive. Because there is relatively little harm to others, there is unlikely to be a movement analogous to the anti-smoking movement. So what are the prospects?

One source of hope is the availability of apps and devices to control Internet use, for example apps to shut down access after a specified time. But even to use such apps requires a degree of self-awareness. Ultimately, the culture of Internet use needs to change. If checking a phone while talking face-to-face with a friend were seen as extremely discourteous, there is some hope, but only if talking face-to-face remains common. Perhaps things will have to become much worse before major efforts are made to change social expectations.

Imagine that all children learn, at home and in school, the characteristics of addictive behaviour and how to change habits. Imagine people becoming more self-aware of their own damaging or time-wasting habits. Imagine companies becoming more responsible. If you’ve come this far, you have a good imagination and maybe you’re just dreaming.

Brian Martin

bmartin@uow.edu.au