Sappho, Ancient Greek poet

“Western civilisation” can be a contentious topic, in part because people interpret it in different ways. Many achievements have been attributed to “the West,” but it has many negatives too. It is not obvious how to assign responsibility for the positives and negatives. Often left out of debates about Western civilisation are alternatives and strategies to achieve them.

In some circles, if you refer to Western civilisation, people might think you are being pretentious, or wonder what you’re talking about. For some, though, the two-word phrase “Western civilisation” can pack an emotional punch.

Western civilisation can bring to mind famous figures such as Socrates, Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci — maybe even some women too — and high-minded concepts such as democracy and human rights. Increasing affluence fits in somewhere. Western civilisation is also associated with a sordid history of slavery, exploitation, imperialism, colonialism and warfare.

My aim here is to outline some of the issues involved.[1] I write this not as an expert in any particular relevant area, but rather as a generalist seeking to understand the issues. Whatever “Western civilisation” refers to, it is a vast topic, and no one can be an expert in every aspect. One of the areas I’ve studied in some depth is controversies, especially scientific controversies like those over nuclear power, pesticides and fluoridation. Some insights from controversy studies are relevant to debates over Western civilisation.

After outlining problems in the expression “Western civilisation,” I give an overview of positives and negatives associated with it. This provides a background for difficult questions concerning responsibility and implications.

Western? Civilisation?

In political and cultural discussions, “the Western world” has various meanings. It is often used to refer to Europe and to other parts of the world colonised by Europeans. This is just a convention and has little connection with the directions east and west, which in any case are relative. Europe is in the western part of the large land mass called Eurasia, so “Western” might make sense in this context. But after colonisation, some parts of the world elsewhere are counted as part of the “West,” including the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. These are called settler colonies, where the immigrants from Europe eventually outnumbered the native inhabitants. However, South and Central American countries are also settler colonies but are less often listed as part of the West. So there is a bit of arbitrariness in defining the West.

The word “civilisation” has different meanings, and sometimes multiple meanings, in different contexts. For historians, civilisation refers to a complex society with established institutions such as governments, laws, commerce and rules of behaviour. A civilisation of this sort has a certain size, cohesion and organisation. The Roman empire is called a civilisation; hunter-gatherer societies are not.[2]

“Civilisation” also refers to being civilised, as opposed to being savage.[3] Being civilised suggests being rational and controlled rather than emotional and chaotic. It also suggests civility: politeness rather than crudity. A civilised person dresses properly, speaks appropriately and knows what rules to obey.

Because the word civilisation has multiple meanings and connotations, which vary from person to person, from context to context and from one time to another, some discussions about it mix emotional and logical matters. Contrary to its positive connotations, a civilisation, in the scholarly meaning, is not necessarily a good thing: it might be a dictatorial exploitative empire. In the everyday meaning of being civilised, it sounds better than being uncivilised. Empires that have caused unspeakable suffering sound better when they are called civilisations. Some mass murderers are, in everyday interactions, polite, rational and well-dressed: being civilised in this sense is no guarantee of moral worth.

Civilised?

Positives

Many of the features of human society that today are widely lauded were first developed in the West or were developed most fully in the West. These might be called the achievements or contributions of Western civilisation.

The ancient Greeks developed a form of collective decision-making in which citizens deliberated in open forums, reaching agreements that then became policy or practice.[4] This is commonly called democracy. In ancient Greece, women, slaves and aliens were excluded from this process, but the basic idea was elaborated there.

Many centuries later, several revolutions (including those in France and the US) overthrew autocracies and introduced a form of government in which citizens voted for representatives who would make decisions for the entire community. This was quite unlike democracy’s roots in ancient Greece, but today it is also commonly called democracy, sometimes with an adjective: liberal democracy or representative democracy. Voting initially was restricted to white male landowners and gradually extended to other sectors of the population.

Commonly associated with representative government are civil liberties: freedom of speech, freedom of association, freedom from arbitrary search, arrest and detention, freedom from cruel treatment. These freedoms, or rights, resulted from popular struggles against tyranny, and are commonly seen as a special virtue of the West, a model for the rest of the world. Struggles over these sorts of freedoms continue today, for example in campaigns against discrimination, surveillance, slavery and torture.

Another contribution from the West is art and, more generally, cultural creations, including architecture, sculpture, painting, music, dance and writing. While artistic traditions are found in societies across the world, some of these, for example ballet and classical music, have been developed in the West to elaborate forms that require enormous expertise at the highest levels, accompanied by long established training techniques for acquiring this expertise.[5]

In the West, manners have evolved in particular ways. On formal occasions, and in much of everyday behaviour, people are mostly polite in speech, conventional in dress, proper in their manner of eating, and modest in their excretions.[6]

The industrial revolution had its home in the West. The development and use of machinery, motorised transport, electricity and many other technological systems have made possible incredible productivity and greatly increased living standards. This has involved inventions and their practical implementation, namely innovation. The West has contributed many inventions and excelled in the process of innovation.

Modern systems of ownership, commercial exchange and employment, commonly called capitalism, developed most rapidly and intensively in the West and were then exported to the rest of the world.

Questioning the positives

The positives of Western civilisation can be questioned in two ways: are they really Western contributions, and are they really all that good?

Representative government is commonly described as “democracy,” but some commentators argue that it is a thin form of democracy, more akin to elected tyranny. It has little resemblance to democracy’s Athenian roots. The ancient Greeks used random selection for many official positions, with a fairly quick turnover, to ensure that those selected did not acquire undue power. This was in addition to the assembly in which every citizen could attend and vote. Arguably, the ancient Greeks had a more developed form of “direct democracy,” direct in the sense of not relying on elections and representatives.[7]

The kleroterion, used for randomly selecting officials in ancient Athens

However, if direct democracy is seen as the epitome of citizen participation, then note should be made of numerous examples from societies around the world, many of them long predating agriculture. Many nomadic and hunter-gatherer groups have been egalitarian, with no formal leaders.[8] They used forms of consensus decision-making that are now prized in many of today’s social movements. There are examples of societies with non-authoritarian forms of decision-making in Africa, Asia and the Americas.

The Iroquois Confederacy in North America had a well-developed decision-making process that predated white American settlers by hundreds of years and, via Benjamin Franklin, helped inspire US democratic principles and methods.[9] A full accounting of the contributions of non-Western societies to models of governance remains to be carried out.[10]

Modern-day civil liberties are needed to counter the repressive powers of the state. However, in egalitarian societies without states, civil liberties are implicit: members can speak and assemble without hindrance. From this perspective, “civilisation” involves citizens of a potentially repressive state congratulating themselves for managing to have a little bit of freedom.

The industrial revolution is commonly attributed to the special conditions in Europe, especially Britain. This can be questioned. It can be argued that Western industrial achievements were built on assimilating superior ideas, technologies and institutions from the East.[11]

As for the West’s cultural achievements, they need to be understood in the context of those elsewhere. Think of the pyramids in Egypt, the work of the Aztecs, the Taj Mahal. Think of highly developed artistic traditions in India, China and elsewhere.

Negatives

Western societies have been responsible for a great deal of killing, exploitation and oppression. Colonialism involved the conquest over native peoples in the Americas, Asia, Africa and Australasia. Europeans took possession over lands and expelled the people who lived there. In the course of European settlement, large numbers of indigenous people were killed or died of introduced diseases. The death toll was huge.[12]

In imperialism, which might be called non-settler colonialism, the European conquerors imposed their rule in damaging ways. They set up systems of control, including militaries, government bureaucracies and courts, that displaced traditional methods of social coordination and conflict resolution. They set up administrative boundaries that took little account of previously existing relationships between peoples. In South America, the administrative divisions established by Spanish and Portuguese conquerors became the basis for subsequent independent states.[13] In Rwanda, the Belgian conquerors implemented a formal racial distinction between Tutsis and Hutus, installing Tutsis in dominant positions, laying the basis for future enmity.[14]

Imperialism had a devastating impact on economic and social development. British rule over India impoverished the country, leading to a drastic decline in India’s wealth, while benefiting British industry.[15] Much of what was later called “underdevelopment” can be attributed to European exploitation of colonies.[16]

Another side to imperialism was slavery. Tens of millions of Africans were captured and transported to the Americas. Many died in the process, including millions in Africa itself.[17]

Imperialism and settler colonialism were responsible for the destruction of cultures around the world. The combination of conquest, killing, disease, exploitation, dispossession, divide-and-rule tactics and imposition of Western models undermined traditional societies. Some damaging practices were imported, including alcohol, acquisitiveness and violence. When Chinese leaders made attempts to stop opium addiction, British imperialists fought wars to maintain the opium trade. Colonial powers justified their activities as being part of a “civilising mission.”

It should be noted that many traditional cultures had their bad sides too, for example ruthless oppressors and harmful practices, including slavery and female genital mutilation. In some respects, Western domination brought improvements for populations, though whether these same improvements could have been achieved without oppression is another matter.

Colonialism was made possible not by cultural superiority but by superior military power, including weapons, combined with a willingness to kill. Europeans were able to subjugate much of the world’s population by force, not by persuasion or example.

In the past couple of centuries, the West has been a prime contributor to the militarisation of the world. Nuclear weapons were first developed in the West, and hold the potential for unparalleled destruction, a threat that still looms over the world. The only government to voluntarily renounce a nuclear weapons capacity is South Africa.

The problems with capitalism have been expounded at length. They include economic inequality, unsatisfying work, unemployment, consumerism, corporate corruption, encouragement of selfishness, and the production and promotion of harmful products such as cigarettes. Capitalist systems require or encourage people to move for economic survival or advancement, thereby breaking down traditional communities and fostering mental problems.

Industrialism, developed largely in the West, has had many benefits, but it also has downsides. It has generated enormous environmental impacts, including chemical contamination, species extinction and ocean pollution. Global warming is the starkest manifestation of uncontrolled industrialism.

Responsibility

What is responsible for the special features of Western civilisation, both positive and negative? One explanation is genetics. Western civilisation is commonly identified with white populations. Do white people have genes that make them more likely to create great works of art, or to be inventors, entrepreneurs or genocidal killers?

The problem with genetic explanations is that gene distributions in populations are too diverse to provide much guidance concerning what people do, especially what they do collectively. There is no evidence that Mozart or Hitler were genetically much different from their peers. There is too much variation between the achievements of brothers and sisters to attribute very much to genetics. Likewise, the rise and fall of civilisations is far too rapid for genetics to explain very much.

Stalin: genetically different?

More promising is to point to the way societies are organised. Social evolution is far more rapid than genetic evolution. Are the social structures developed in the West responsible for its beneficial and disastrous impacts?

The modern state is commonly said to have developed in Europe in the past few hundred years, in conjunction with the rise of modern military systems. To provide income for its bureaucratic apparatus, the state taxed the public, and to enforce its taxation powers, it expanded its military and police powers.[18] A significant step in this process was the French Revolution, which led to the development of mass armies, which proved superior to mercenary forces. The state system was adopted in other parts of the world, in part via colonialism and in part by example.

The state system can claim to have overcome some of the exploitation and oppression in the previous feudal system. It has also enabled massive investments in infrastructure, including in military systems, creating the possibility of ever more destructive wars as well as extensive surveillance. The French revolution also led to the introduction of the world’s first secret police, now institutionalised in most large states.[19]

If the West was the primary contributor to the contemporary state system, this is not necessarily good or bad. It has some positives but quite a few negatives.

A role for chance?

Perhaps what Western civilisation has done, positive and negative, shows nothing special about Western civilisation itself, but is simply a reflection of the capacities and tendencies of humans. Had things been a bit different, the same patterns might have occurred elsewhere in the world. In other words, the triumphs and tragedies of Western civilisation should be treated as human triumphs and tragedies, rather than reflecting anything special about people or institutions in the West.

On the positive side, it is apparent that people from any part of the world can attain the highest levels of achievement, whether in sport, science, heroism or service to the common good. The implication is that, in different circumstances, everything accomplished by lauded figures in the West could have been done by non-Westerners. Of course, there are many examples where this is the case anyway. Major steps in human social evolution — speech, fire, tools, agriculture — are either not attributed to a particular group, or not to the West. These developments are usually said to reflect human capacities. So why not say the same about what is attributed to a “civilisation”?

The same assessment can be made of the negatives of Western civilisation, including colonialism, militarism and industrialism. They might be said to reflect human capacities. Genocides have occurred in many parts of the world, and nearly every major government has set up military forces. Throughout the world, most people have eagerly joined industrial society, at least at the level of being consumers.

When something is seen as good, responsibility for it can be assigned in various ways. Leonardo da Vinci is seen as a genius. Does this reflect on him being a man or a person with opportunities? Is being white important? How should responsibility be assigned to the emergence of Hitler or Stalin?

Research on what is called “expert performance” shows that great achievements are the result of an enormous amount of a particular type of practice, and suggests that innate talent plays little role.[20] The human brain has enormous capacities, so the key is developing them in desirable ways. On the other hand, humans have a capacity for enormous cruelty and violence, and for tolerating it.[21]

Alternatives

For those critical of state systems, militarism and capitalism — or indeed anything seen as less than ideal — it is useful to point to alternatives.

One alternative is collective provision, in which communities cooperate to provide goods and services for all. This is a cooperative model, in contrast with the competitive individualistic model typical of capitalist markets.[22] In collective provision, “the commons” plays a key role: it is a facility available to all, like public libraries and parks. Online examples of commons are free software and Wikipedia, which are created by volunteers and available to all without payment or advertisements. Applied to decision-making, deliberative democracy is an alternative close to the cooperative approach.

The rise of capitalism involved the enclosure of lands that were traditionally used as commons. “Enclosure” here means takeover by private or government owners, and exclusion of traditional users. Contemporary proponents of the commons hark back to earlier times, before the enclosure process began.

Free software is a type of commons.

What is significant here is that commons historically, as highly cooperative spaces, developed in many places around the world. They are not a feature of a particular civilisation.

Another alternative is strategic nonviolent action, also called civil resistance.[23] Nonviolent action involves rallies, marches, strikes, boycotts, sit-ins and various other methods of social and political action. Nonviolent action is non-standard: it is defined as being different from conventional political action such as voting and electoral campaigning.

Social movements — anti-slavery, feminist, peace and environmental movements, among others — have relied heavily on nonviolent action. Studies show that nonviolent movements against repressive regimes are more likely to be effective than armed resistance.[24] Compared to the use of violence, nonviolent movements have many advantages: they enable greater participation, reduce casualties and, when successful, lead to greater freedom in the long term.

People have been using nonviolent action for centuries. However, the use of nonviolent action as a strategic approach to social change can be attributed to Mohandas Gandhi and the campaigns he led in South Africa and India.[25] Strategic nonviolent action has subsequently been taken up across the world.

Gandhi

So what?

Why should it make any difference whether Western civilisation is judged for its benefits or its harms? Why should people care about something so amorphous as “Western civilisation”?

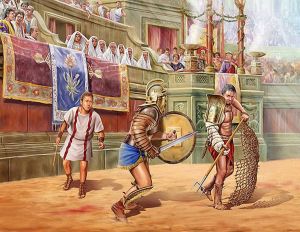

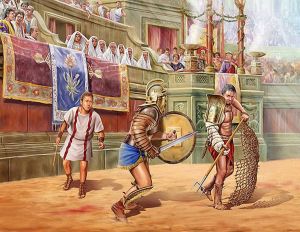

Most people who live and work in Western countries make little significant contribution to something as massive as a civilisation. They might be likened to observers, analogous to spectators at a sporting match. Logically, there is no particular virtue in being a fan of a winning team. Similarly, there should be no particular glory in touting the achievements of the “civilisation” in which one lives. In practice, though, it seems as if some protagonists in the debate over Western civilisation do indeed identify with it.

Spectators watching gladiators

This is a psychological process called honour by association. It is apparent in all sorts of situations, for example when you tell others about the achievements of your family members or about meeting a famous person. There can be honour by association via the suburb in which you live, your occupation, your possessions, even the food you eat.

The point about honour by association is that, logically, it is not deserved. When, as a spectator, you bask in the glory of a winning team, you’ve done nothing particular noteworthy, aside perhaps from being part of a cheering crowd. The same can apply to being associated with the greatest accomplishments in the history of Western civilisation. If you are part of a long tradition of artistic, intellectual or entrepreneurial achievement, it sounds nice but says nothing about what you’ve done yourself. It is only honour by association.

The same applies to guilt by association, which might also be called dishonour by association. If your ancestors were racists or genocidal killers, why should that reflect on you?[26]

Another way to think about this is to note that no one chooses their own parents. Growing up as part of the culture in which one was born shows no special enterprise and should warrant no particular praise. Emigrants often show more initiative. For various reasons, they are not content with their place of birth and seek out more desirable locations to spend their lives and rear their children.

Why study Western civilisation?

Why study anything? Learning, in a systematic and rigorous fashion, has impacts independent of the subject studied. On the positive side, students learn how to think. In the humanities, they learn to think critically and to communicate in writing and speech. On the negative side, or ambiguously, they learn how to play the academic game, to be willing to subordinate their interests to an imposed syllabus, and to be obedient. Formal education has been criticised as preparation for being a reliable and obedient employee.[27]

More specifically, is there any advantage in studying Western civilisation rather than some other speciality? Proponents say students, and citizens, need to know more about the ideas and achievements that underpin the society in which they live. This is plausible. Critics say it is important to learn not only about the high points of Western civilisation but also about its dark sides. Many of the critics do precisely this, teaching about the history and cultural inheritance of colonialism and capitalism. Their concern about focusing on the greatest contributions from the West is that the negative sides receive inadequate attention.

There is another possible focus of learning: alternatives, in particular alternatives to current institutions and practices that would go further in achieving the highest ideals of Western and other cultures. For example, democracy, in the form of representative government, is studied extensively, but there is little attention to participatory alternatives such as workers’ control.[28] Formal learning in classrooms is studied extensively, but there is comparatively little attention to deprofessionalised learning.[29] Examples could be given in many fields: what exists is often taken as inevitable and desirable, while what does not exist is assumed to be utopian.

The next step after studying alternatives is studying strategies to move towards them. This is rare in higher education, though it is vitally important in social movements.[30]

Why study Western civilisation? One answer is to say, sure, let’s do it, but let’s also study desirable improvements or alternatives to Western civilisation, and how to bring them about.

Controversies over Western civilisation

Some controversies seem to persist indefinitely, regardless of arguments and evidence. The debate over fluoridation of public water supplies has continued, with most of the same claims, since the 1950s. There are several reasons why resolution of debates over Western civilisation is difficult.[31]

One factor is confirmation bias: people preferentially seek out information that supports their existing views, and they find reasons to dismiss or ignore contrary information.[32]

A second factor is the burden of proof. Typically, partisans on each side in a controversy assign responsibility to the other side for proving its case.

A third factor is paradigms, which are coherent sets of assumptions, beliefs and methods. The paradigms underpinning history and sociology are quite different from those used in everyday life.

A fourth factor is group dynamics. In polarised controversies, partisans mainly interact with those with whom they agree, except in hostile forums such as public debates.

A fifth factor is interests, which refer to the stakes that partisans and others have in the issues. Interests include jobs, profits, reputation and self-esteem. Interests, especially when they are substantial or “vested,” can influence individuals’ beliefs and actions.

The sixth and final factor is that controversies are not just about facts: they are also about values, for example about ethics and decision-making. This is true of scientific controversies and even more so of other sorts of controversies.

The upshot is that in a polarised controversy, partisans remain set in their positions, not budging on the basis of the arguments and evidence presented by opponents. It is rare for a leading figure to change their views. It is fairly uncommon for a partisan to try to spell out the strongest arguments for the contrary position. Instead, partisans typically highlight their own strongest points and attack the opponent’s weakest points.

My observation is that all these factors play a role in debates over Western civilisation. It is safe to predict that disagreements are unlikely to be resolved any time soon.

Acknowledgements

Over the years, many authors and colleagues have contributed to my understanding of issues relevant to this article.

Thanks to all those who provided comments on drafts: Paula Arvela, Anu Bissoonauth-Bedford, Sharon Callaghan, Lyn Carson, Martin Davies, Don Eldridge, Susan Engel, Anders Ericsson, Theo Farrell, Zhuqin Feng, Kathy Flynn, Xiaoping Gao, John Hobson, Dan Hutto, Bruce Johansen, Dirk Moses, Rosie Riddick, Nick Riemer, Denise Russell, Jody Watts, Robert Williams, Qinqing Xu and Hsiu-Ying Yang. None of these individuals necessarily agrees with anything in the article, especially considering that many commented only on particular passages.

Further comments are welcome, including suggestions for improving the text.

Brian Martin

bmartin@uow.edu.au

Footnotes

[1] My motivation for addressing this topic is the introduction of a degree in Western civilisation at the University of Wollongong and the opposition to it. I commented on this in “What’s the story with Ramsay?”, 7 March 2019, https://comments.bmartin.cc/2019/03/07/whats-the-story-with-ramsay/

[2] Thomas C. Patterson, Inventing Western Civilization (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1997), says the concept of civilisation, from the time it was first formulated in the 1760s and 1770s, has always referred to societies having a state and hierarchies based on class, sex and ethnicity. Often there is an accompanying assumption that these hierarchies are natural.

[3] On the idea of the savage as an enduring and damaging stereotype that serves as the antithesis of Western civilisation, see Robert A. Williams, Jr., Savage Anxieties: The Invention of Western Civilization (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

[4] Mogens Herman Hansen, The Athenian Democracy in the Age of Demosthenes: Structure, Principles and Ideology (Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell, 1991); Bernard Manin, The Principles of Representative Government (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

[5] Western classical music is not inherently superior to, say, Indian, Chinese, Japanese or Indonesian music. However, musical notation and public performance led in Western Europe to distinctive methods for training elite performers.

[6] Norbert Elias, The Civilizing Process: The History of Manners, volume 1 (New York: Urizen Books, 1978; originally published in 1939).

[7] David Van Reybrouck, Against Elections: The Case for Democracy (London: Bodley Head, 2016).

[8] Harold Barclay, People without Government (London: Kahn & Averill, 1982).

[9] For an account of academic and popular resistance to the idea that the Iroquois Confederacy influenced the US system of democracy, see Bruce E. Johansen with chapters by Donald A. Grinde, Jr. and Barbara A. Mann, Debating Democracy: Native American Legacy of Freedom (Santa Fe, NM: Clear Light Publishers, 1998).

[10] See Benjamin Isakhan and Stephen Stockwell, eds., The Edinburgh Companion to the History of Democracy (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012) for treatments of pre-Classical democracy, and much else.

[11] John M. Hobson, The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

[12] John H. Bodley, Victims of Progress (Menlo Park, CA: Cummings, 1975).

[13] Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1991, revised edition).

[14] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001).

[15] Shashi Tharoor, Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India (London: Penguin, 2017).

[16] Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (Washington, DC: Howard University Press, 1974).

[17] For a detailed account of the horrors of colonialism in the Congo, and of the struggles to set the narrative about what was happening, see Adam Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998).

[18] Bruce D. Porter, War and the Rise of the State: The Military Foundations of Modern Politics (New York: Free Press, 1994); Charles Tilly, Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990–1992 (Cambridge MA: Blackwell, 1992).

[19] Thomas Plate and Andrea Darvi, Secret Police: The Inside Story of a Network of Terror (London: Sphere, 1983).

[20] Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool, Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise (London: Bodley Head, 2016).

[21] Steven James Bartlett, The Pathology of Man: A Study of Human Evil (Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 2005).

[22] Nathan Schneider, Everything for Everyone: The Radical Tradition that Is Shaping the Next Economy (New York: Nation Books, 2018).

[23] Gene Sharp, The Politics of Nonviolent Action (Boston: Porter Sargent, 1973).

[24] Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan, Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict (Columbia UP, New York, 2011).

[25] M. K. Gandhi, An Autobiography or the Story of My Experiments with Truth (Ahmedabad: Navajivan, 1940, second edition).

[26] This is different from institutional responsibility. When politicians give apologies for crimes committed by governments, they do so as representatives of their governments, not as personal perpetrators.

[27] Jeff Schmidt, Disciplined Minds: A Critical Look at Salaried Professionals and the Soul-battering System that Shapes their Lives (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000).

[28] Immanuel Ness and Dario Azzellini, eds., Ours to Master and to Own: Workers’ Control from the Commune to the Present (Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books, 2011).

[29] Ivan Illich, Deschooling Society (London: Calder and Boyars, 1971).

[30] For example, Chris Crass, Towards Collective Liberation: Anti-racist Organizing, Feminist Praxis, and Movement Building Strategy (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2013)

[31] This section draws on ideas outlined in my article “Why do some scientific controversies persist despite the evidence?” The Conversation, 4 August 2014, http://theconversation.com/why-do-some-controversies-persist-despite-the-evidence-28954. For my other writings in the area, see “Publications on scientific and technological controversies,” https://www.bmartin.cc/pubs/controversy.html.

[32] Raymond S. Nickerson, “Confirmation bias: a ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises,” Review of General Psychology, 2(2), 1998, pp. 175–220.